Kyle MacDonnell became one of TV ‘s very first stars in the late 1940s. Between 1948 and 1951 she hosted a number of shows and made guest appearances on many others. She took a break from show business in 1951 to have a baby and her career never recovered. Kyle died in 2004, her role as a TV pioneer all but forgotten.

Television Comes Of Age

The television industry in the United States, like the rest of the country, threw itself into the war effort following the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. The nation entered World War II a little over five months after commercial television was officially introduced on July 1st. When the war ended, attention turned to expanding the reach of television, improving the quality of its broadcasts and most importantly convincing both sponsors and the public that the new medium was here to stay.

Network television became a reality in 1947 — with small but growing networks broadcasting first on the East Coast and later on a separate network in the Midwest — linking individual stations together and allowing increasingly large audiences to view programs at the same time. Production values were limited both by budget and technology. Much of what was seen on the air was adapted from vaudeville or radio as producers, directors and actors (and viewers) got a feel for what worked and what didn’t.

Although still in its infancy, television was growing fast. “The chances are,” declared Time in May 1948, “it will change the American way of life more than anything since the Model T” [1]. Change it did. There is no better example of the power of television than the story of Kyle MacDonnell, a model, stage actress, and singer who quickly became one of it’s very first stars and just as quickly was entirely forgotten.

Early Life

Ruth Kyle MacDonnell was born on May 13th, 1922 in Austin, Texas to George and Donna MacDonnell [2]. Her great-great-grandfather was Edward Burleson, who served as vice-president of the Republic of Texas from 1841 to 1844. She was known throughout her career as Kyle, which was a family name on her father’s side.

When she was five, her family moved to Larned, Kansas. She later attended the Ward-Belmont School for Women in Nashville, Tennessee. Around the age of 16, Kyle contracted tuberculosis and was confined to her bedroom for close to four years. It was there that she began to develop her musical skills, listening to the radio every night and learning to imitate the styles of various singers.

After recovering from her illness, Kyle enrolled at Kansas State College and later returned to Ward-Belmont for post-graduate work. Some of her classmates entered her into a contest to pick Miss Air Transport Command. One of the judges was Harry Conover, owner of the famous Conover Modeling Agency in New York City. She won the contest and Conover suggested she become a model.

Kyle demurred, more interested in a career as a singer. In November 1945 she was in New York City to watch the annual Army-Notre Dame football game and ran into Conover at a party. He again offered her a modeling contract and this time she accepted it.

Kyle Gets Her Start

Her modeling career paid the bills. “My teeth and my feet kept me from starving,” she recalled in 1951. “I posed for toothpaste ads and shoe ads” [3]. In December 1945, Kyle was chosen Miss San Antonio by the Texas Club of New York to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Texas becoming a state [4]. In July 1946, she participated in a contest to find the best feet among New York City models and was a runner up [5].

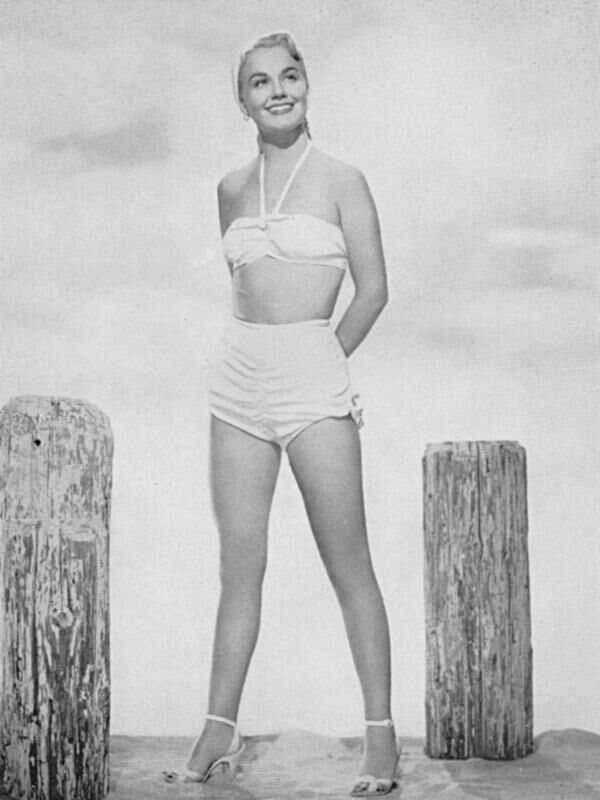

Copyright © G & E Publishing Co., Inc., 1949 [1]

Later that year, Kyle got a small role in the Broadway musical Park Avenue , reportedly due to producer Max Gordon seeing her in a toothpaste ad [6]. She would later credit a theatrical agent for securing the role [7]. The musical was written by George S. Kaufman and Nunnally Johnson, with music by Arthus Schwartz and lyrics by Ira Gershwin.

Park Avenue opened on November 6th, 1946. Despite its pedigree, the production not a success, and closed after 72 performances on January 4th, 1947. It was Gershwin’s last work for Broadway but for Kyle MacDonnell it was seemingly a big break. She was signed to a six-month movie contract with Warner Brothers in May 1947, turning down offers from three Broadway plays, and moved to Hollywood [8].

Shortly thereafter, she was given her first role, a small part in That Hagen Girl (originally titled Mary Hagen) starring Shirley Temple and Ronald Reagan. To prepare for the role and to learn more about acting, Kyle studied with dramatic coaches to learn diction. She told John L. Scott of The Los Angeles Times she didn’t know if she’d make it in the movies, and worried about what she’d do if she didn’t:

My contract has six-month options. October will tell the story whether the powers-that-be feel I have a good chance as a film player, or not. The only trouble is that I would like to take up offers to do either ‘Allegro’ or ‘Auld Lang Syne’ in New York–and they will probably be fully cast by October. So here’s hoping I make the grade in pictures.

I have noticed that several of the newer people in films have famous sponsors. I have none. While John F. Royal, the radio executive, is a good friend of the family, his medium is not, unfortunately, movies. [9]

Hedging her bets, Kyle got a part in another musical while on the West Coast waiting to become a movie star, appearing in the Los Angeles Civic Light Opera’s production of Louisiana Purchase, which opened in July 1947. It was a smart move. Her role in That Hagen Girl wound up being cut from the film. “You might have seen me in a single scene,” she said later, “if you watched closely and didn’t blink” [10]. Her movie career was over before it started.

Later that year, she flew back to New York City to audition for a role in Make Mine Manhatten, a new Broadway revue starring Sid Caesar. She got the part of a singing ingenue and was back on Broadway. Make Mine Manhatten opened on January 15th, 1948.

The Move To Television

Like so much of her career, Kyle MacDonnell’s early days in television are murky. Her very first television appearance likely came less than two weeks after Make Mine Manhatten opened on Broadway. On Tuesday, January 27th, 1948 the CBS station in New York City (WCBS-TV) broadcast the 4th Annual New York Dress Institute Fashion Show for March of Dimes. Held at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, the fundraiser benefited the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis. It began at 1:30PM and featured both fashion and entertainment. Along with other Broadway stars, Kyle provided commentary during a portion of the show [11].

By all accounts, it was her role in Make Mine Manhatten the led Kyle to the small screen. According to director Ira Skutch, NBC television executive John F. Royal (a friend of the MacDonnell family) saw her on Broadway one night and the very next day set up a live television audition for her [12].

NBC’s New York City station, WNBT, went on the air at 7:30PM just for the audition, which ran for seven minutes and involved Kyle singing a few songs. Royal liked what he saw and Kyle soon made a few guest appearances on NBC’s Musical Merry-Go-Round, a live music series hosted by Jack Kilty (who coincidentally co-starred with Kyle in Make Mine Manhatten) [13]. Before long, she had her own show on NBC, a 15-minute musical/variety series called For Your Pleasure that premiered in April.

Exactly when her audition took place is unknown. It had to have occured after Make Mine Manhatten opened on Broadway in January 1948 but prior to the debut of For Your Pleasure in April 1948. Likewise, it is unclear how many episodes of Musical Merry-Go-Round she appeared on. They, too, had to have taken place prior to April 1948.

According to May 31st issue of Life, Kyle made just five guest appearances on television before getting her own show [14]. If true, she may have appeared on Musical Merry-Go-Round five times between January and April 1948.

Kyle may also have appeared on television during the 2nd Annual Antoinette Perry Awards (better known today as the Tony Awards) held in New York City on Sunday, March 28th. Along with her Make Mine Manhatten co-star Joshua Shelley, she performed during the ceremony, which was broadcast by DuMont station in New York City, WABD, and potentially over the entire DuMont network in existence at that point [15].

Counting her audition, it appears Kyle was before television cameras fewer than 10 times before she was given her own TV series, all within the span of four months and all while she was also appearing on Broadway nearly every day.

For Your Pleasure

Kyle’s first television series premiered on Thursday, April 15th, 1948 at 8PM on NBC. It was a live musical/variety show and lacked a sponsor. Each episode ran for 15 minutes and was shot on a studio set made to look like a nightclub. Kyle served as mistress of ceremonies as well as the lead performer, backed by the Norman Paris Trio. Also featured was the dance duo Jack and Jill, who were replaced at some point in June 1948 by another dance team, Blaire and Deane [16]. Fred Coe served as director and Frank Burns technical director.

Sam Chase reviewed the premiere episode in the May 1st issue of The Billboard. The only live music was a pianist, suggesting the Norman Paris Trio did not appear in the debut. Kyle sang two songs — “How High the Moon” and “I Wish I Didn’t Love You So” — during the episode.

Chase called Kyle “an extremely photogenic personality with grace and naturalness, who was charming even in a sign-off announcement fluff” and felt she “may well prove an important video find” [17]. Dancers Jack and Jill gave a “routine” performance while comic Dan Henry suffered from poor camera work and a “tendancy to mug too much” [18]. The network, he concluded, “has a sure-fire hit in Miss McDonnell [sic], and should it surround her with proper support in the future, can have a pleasing airer in this slot” [19].

Copyright © U.S.A. Com. Magazine Corp, 1948 [2]

Critic Jack Gould gave Kyle MacDonnell an even more glowing review in the May 2nd issue of The New York Times, after just three episodes of For Your Pleasure had aired. He called her “television’s first truly new and bright star” who “has emerged as far and away the most ‘videogenic’ young lady yet seen before the cathode cameras” [20]. He also praised the “freshness and natural beauty” through which she “projects a warmth and friendliness which capitalize to the hilt on the factor of intimacy that is video at its most effective” [21]. Gould continued:

But it is in her singing that Miss MacDonnell has most immediately carved a niche for herself. If on stage her voice is a little weak, on television the amplifying qualities of the microphone stand her in good stead. Her mezzo-soprano comes over true and clear yet in a straight torch number she can inject a meaningful sultriness which is box-office plus. Thanks to her theatrical training, she also knows what to do with her face during a number, something that cannot be said for many feminine vocalists accustomed to the unseeing microphone. Her change of expression compliments rather than contradicts the lyrics. All in all, Miss MacDonnell is providing that rare treat among performances–the vivacity of youth combined with professional stage presence. [22]

Gould was also critical in his review, although not of Kyle herself. The Norman Paris Trio, he wrote, “suffered from a certain sameness which might be alleviated by more attention to the melody and less to tricky effects” [23]. There were problems, too, with the quality of the lighting, which ranged from “almost blotting out Miss MacDonnell and the other artists in a haze of whiteness and at other moments reflecting both skill and thought” [24]. He was certain, however, that additional rehearsal time would alleviate such problems.

(Somewhat less impressed with Kyle was WNBT’s Ira Skutch, who referred to her as “a tall, willowy, pretty blond” who “sang well — not great” [25].)

Almost overnight, For Your Pleasure turned Kyle MacDonnell into one of television’s first stars. It helped that there weren’t a lot of shows like hers on the air. A ban on live music on television, implemented by the American Federation of Musicians in February 1945, was lifted less than a month before For Your Pleasure debuted. The networks immediately set about translating their hit radio shows to television. As Jack Gould indicated, however, not every radio performer was able to transition to television.

The May 28 issue of Time included an article about the growing influence of television and its future, featuring a photograph of Kyle MacDonnell. Most singers, the article concluded, were uncomfortable at the prospect of appearing on television and found the “telecamera’s unwinking stare an embarrassing experience” [26]. But not Kyle. She was a notable exception and “was already becoming television’s No. 1 pin-up girl” [27].

Days later, Kyle graced the cover of the May 31st issue of Life. Inside, a brief paragraph explained her success:

Kyle MacDonnell […] has what is known flatteringly in television circles as “a living-room quality.” This is a cross between professional stage presence and conversational intimacy, between American girlishness and blond sexiness. Her catch-all appeal nets strangely assorted fan mail from grandmothers, grammar-school kids and ardent bachelors. [28]

In July, The Billboard declared television capable of “making stars out of personalities either new to show business or who have batted about in other branches before achieving recognition in tele” [29]. Kyle was named as an example, alongside Bob Smith, Gil Fates, Mary Kay Stearns, Bob Emery and others. They were said to be the names “widest known to viewers in the present and nearest future. They are the first tele luminaries who may be remembered as pioneer stars in years to come” [30].

For Your Pleasure was given a special Wednesday airing on June 23rd from 8:15-8:30PM due to a scheduling conflict with coverage of the Republican National Convention on Thursday, June 24th that pre-empted the series. It would move permanently to the Wednesday 8-8:15PM time slot beginning July 7th. The very next week, however, the series was pre-empted by coverage of the Democratic National Convention.

A total of 20 episodes of For Your Pleasure were broadcast between April and September 1948, the last of which aired on September 1st. The following week, Kyle began her second television series, this one with a sponsor.

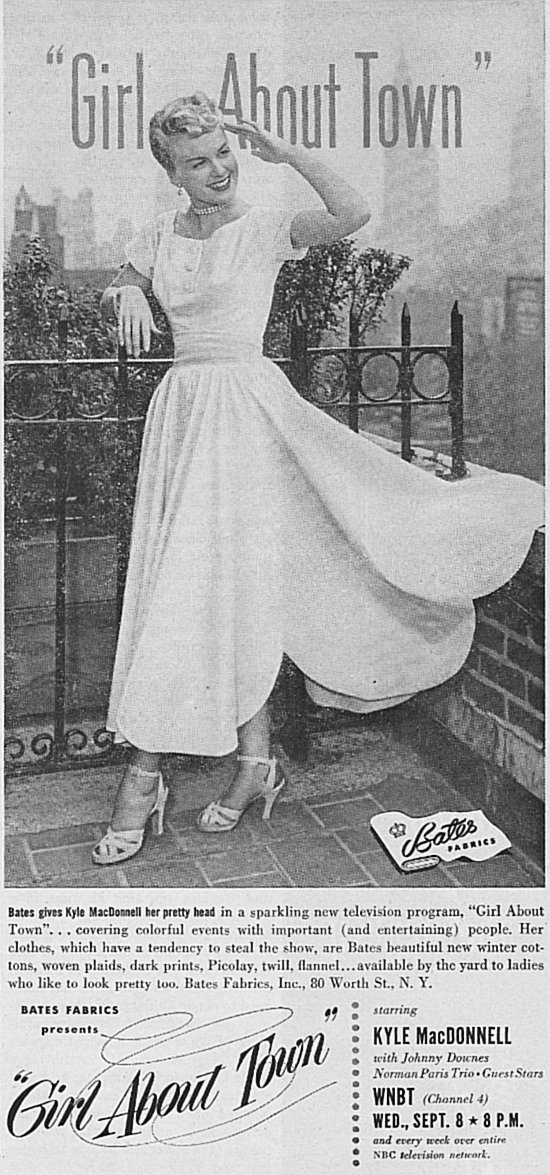

Girl About Town I: A Sponsor Comes Calling

The success of For Your Pleasure and Kyle MacDonnell’s popularity did not go unnoticed by the advertising community. In mid-August 1948, The New York Times reported that Kyle would soon be appearing in a new television series produced for and airing on the NBC television network. Unlike For Your Pleasure, which was broadcast on a sustaining basis, the new show would have a sponsor: Bates Fabrics, Inc. [31]. Bates signed a 52-week contract with NBC for the series, through advertising agency James P. Sawyer, Inc. [32].

The new show would be called Girl About Town. Rather than give viewers the impression that Kyle was performing at a nightclub, as For Your Pleasure had done, Girl About Town would utilize film footage shot around New York City to suggest Kyle was visiting, chatting and singing all over the city. Film actor Johnny Downs would play Kyle’s press agent in charge of booking her appearances.

Copyright © G & E Publishing Co., Inc., 1949 [3]

The series would mark the television debut for Downs [33]. As a child, he co-starred in more than 20 of Hal Roach’s “Our Gang” shorts between 1925 and 1927 before transitioning to adult roles in the mid-1930s, primarily in movie musicals. Like For Your Pleasure, Girl About Town would also feature the Norman Paris Trio.

Did For Your Pleasure transition to Girl About Town in September 1948? Was there an announcement during the final episode of For Your Pleasure, informing viewers that a new series would debut the following week? Or was the change ignored entirely? In any event, the first episode of Girl About Town aired on Wednesday, September 8th and ran from 8-8:20PM, five minutes longer than For Your Pleasure the previous week. Perhaps the extra five minutes was used to fit in commercials for Bates products.

Kyle was on the cover of the November 1948 issue of Bates Magazine, the employee publication for Bates Manufacturing Co. Included was a two-page feature about the show and the use of Bates products on television:

Bates new television program, “Girl About Town,” features the event of the week in Manhattan, has itself become the event of the week over the entire NBC television network! Bates fine made-in-Maine products are an integral pat of the show; each week television audiences see Bates fashion fabrics, bedspreads and matching draperies, and Comb-Percale sheets and pillowcases presented in sparkling settings. Leading stores in seven cities are tying in their own advertising with “Girl About Town”…are making television an even more powerful medium for selling Bates! [34].

The magazine also claimed that Bates was the first company from Maine and the “first important textile concern” to advertise on television [35].

According to Ira Skutch, who served as WNBT’s producer-director on Girl About Town, the advertising manager for Bates made production of the show difficult. “Fancying himself a great impresario,” Skutch recalled, “he involved himself in every detail of the production, insisting on themes for the show that were impossible to produce. Dissension developed between us which I confess I handled in a less than felicitous manner” [36]. Skutch was fired from the show after about ten weeks when he misread the clock and the closing commercial wasn’t aired.

Guests Girl About Town during the fall of 1948 included bandleader Tommy Dorsey, Russell Swan, Randall Weeks, Ellsworth and Fairchild (dancers), Rosario and Antonio (dancers), and Pancho and Diane (dancers). Johnny Downs left the show at some point in October or November 1948, replaced by singer Earl Wrightson [37]. Exactly when or why is unknown.

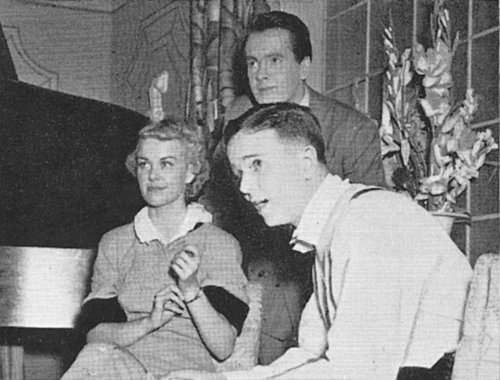

Copyright © Bates Manufacturing Co., 1948 [4]

As she had with For Your Pleasure, Kyle juggled Girl About Town with her commitment to Make That Manhattan on Broadway. Radio and Television Mirror published an overview of her hectic schedule during the fall of 1948: she started every Wednesday with a fitting for Girl About Town, followed by three hours of rehearsals at WNBT and a quick lunch; then she left for a Make Mine Manhattan matinee at the Broadhurst Theatre before returning to WNBT prepare for Girl About Town live broadcast at 8PM; afterwards, she went back to the Broadhurst for the evening Make Mine Manhattan show [38].

Make Mine Manhattan closed in January 1949, making Kyle’s life — or at least her Wednesdays — a little easier.

Girl About Town II: A Murky End

1948 was both television’s year and Kyle’s. As it came to a close, Jack Gould issued his annual Honor Roll in The New York Times, recognizing top performers and programs on radio and television. Milton Berle was declared Outstanding Personality: Male for his television work on NBC’s Texaco Star Theatre. Television had yet to develop a female equivalent to Berle, said Gould, “though for friendliness and informality on the screen Kyle MacDonnell, with both voice and looks, easily headed the list of contenders” [39]. Rather than being called Outstanding, she had to settle for simply Personality: Female.

Copyright © Bates Manufacturing Co., 1948 [5]

The new year brought with it big changes for television. On Tuesday, January 11th, 1949 the separate Eastern and Midwest networks were linked by AT&T coaxial cable. Initially limited to one circuit in each direction, time on the connected networks was shared by the four networks. Girl About Town was not immediately impacted by the expansion of network television. According to Broadcasting, the show would continue to air live on NBC’s Eastern network with repeats via kinescope broadcast from Chicago over Midwest network two weeks later [40].

(It is unclear whether Girl About Town was seen on NBC’s Midwest network via kinescope prior to January 1949. Certainly, it could not have aired live in that part of the country. But even before the two regional networks were linked, kinescopes of NBC programming aired live on its Eastern network were shipped nationwide for rebroadcast. It’s possible that Girl About Town, and before it For Your Pleasure, were broadcast on a delayed basis via kinescope in the Midwest and perhaps even the West Coast.)

On February 19th, The New York Times reported that Girl About Town would move to Sundays at 10:10PM beginning February 27th. This would allow the show to be aired live on both the Eastern and Midwest networks [41]. The first Sunday episode featured the Bates 1949 College Board, a group of college students who worked with Bates to promote its fabrics on college campuses [42].

Four months later, The New York Times reported that Girl About Town would move again, this time to Thursdays at 9PM starting July 7th. It would run for 15 minutes and be called Kyle MacDonnell Sings [43]. The final Sunday broadcast of Girl About Town took place on June 26th. But the move to Thursday never materialized, for reasons unknown.

What is very clear is that Girl About Town was cancelled, either by NBC or by Bates, before its 52-week run was completed. The cancellation likely happened abruptly, leaving NBC scrambling to figure out what do with Kyle. The network either wanted or needed to keep her on the air, perhaps due to contractual obligations or simply because it supported her.

Plans for the Thursday Kyle MacDonnell Sings show were firm enough that the July 7th debut was included in the weekly television listings published in The New York Times on July 3rd (although referred to as The Kyle MacDonnell Show) [44]. The daily listings for July 7th, however, had Candid Camera airing Thursdays at 9PM [45]. Billboard also included The Kyle MacDonnell Show in a chart of network programming for August published on July 25th [46].

Kyle did eventually return to NBC, under a familiar title, but not until late July. A total of 43 episodes of Girl About Town aired between September 1948 and June 1949. Some sources indicate that the name of the show was changed to Around the Town during the last months it was on the air [47].

For Your Pleasure (Again)

On July 28th, some five weeks after Girl About Town went off the air, The New York Times reported that Kyle would debut a new NBC show on Saturday, July 30th [48]. It would replace Television Screen Magazine, an early NBC series that had premiered in November 1946. The show would be called For Your Pleasure, reusing the name of her first NBC show.

The new For Your Pleasure would run a full half-hour from 8:30-9PM, unlike the first which was only 15 minutes long. Like the original incarnation and Girl About Town, it would feature the Norman Paris Trio. Additional music would be provided by the Earl Shelton Orchestra. Richard Goode served as director.

It is not clear if the second incarnation of For Your Pleasure was sponsored. It may have been sustaining, like the first. It definitely was not sponsored by Bates. Each week Kyle would entertain guests. In the first episode, she hosted Mata and Hari, a dance team. Burl Ives was the guest for the August 20th episode.

Just seven episodes of the second version For Your Pleasure were aired, the last of which was broadcast on September 10th, almost exactly a year after Girl About Town premiered. The series was sometimes referred to as Kyle MacDonnell Sings or The Kyle MacDonnell Show, perhaps due to the leftover confusion stemming from the cancellation of Girl About Town.

It would be more than eight months after For Your Pleasure left the air before Kyle returned to weekly television.

Interlude: A Return to Broadway & Cavalcade of Stars

For the first time in almost a year and a half, Kyle didn’t have a television series to host every week. She returned quickly to the theater as a featured performer in a new Broadway revue called Touch and Go. The production’s sketches and lyrics were written by theater critic Walter Kerr and his wife Jean Kerr. The pair’s earlier collaboration, a 1946 Broadway play called The Song of Bernadette, ran for just three performances. Jean Kerr would later write Please Don’t Eat the Daisies in 1957, which was turned into a movie in 1960 and a television series in 1965.

Walter Kerr also directed the revue, which was produced by George Hall and presented by George Abbott, with music by Jay Gorney and choreography by Helen Tamiris. It opened at the Broadhurst Theatre, where Kyle had previously appeared in Make Mine Manhattan, on October 13th, 1949. Kyle appeared in six sketches in the revue, playing the title character in parody of the Cinderella story, Ophelia in a satire of Hamlet, and a glamorous movie star appearing in a scene with a gorilla in which the great ape turns out to be smarter than the leading man.

Brooks Atkinson, reviewing Touch and Go for The New York Times, praised the young cast. Kyle, he wrote, “is radiantly beautiful, has a sense of humor and can sing remarkably well–qualities said to be common to all the women in Texas” [49]. The revue ran for a total of 176 performances, closing on March 18th, 1950. It would be Kyle’s last time on Broadway.

A week later, on Saturday, March 25th, Kyle made the first of five guest appearances on DuMont’s Cavalcade of Stars, hosted by Jerry Lester. Other guests that night included Chester Morris and Dizzy Gillespie. She would then make four consecutive appearances on the series from April 8th to April 22nd. It’s likely that she sang in many or all of these episodes. She also appeared in sketches.

(Lester was the variety show’s second host, having replaced original host Jack Carter less than a month earlier. Carter hosted the series from its debut in June 1949 through February 1950. Lester was himself replaced as host in July 1950 by Jackie Gleason.)

Celebrity Time

A few weeks after her last guest appearance on Cavalcade of Stars, Kyle became a permanent panelist on the CBS game show Celebrity Time. The show had a complicated history involving two networks, a number of name changes, and multiple hosts. It premiered in November 1948 as a local program on WCBS-TV in New York City under the name The Eyes Have It. Within a few weeks its title had changed first to Stop, Look and Listen and then Riddle Me This. Douglas Edward was the first host, replaced almost immediately by Paul Gallico. Conrad Nagel took over as host in December 1948.

The series featured four panelists (typically two men competing against two women) who had to identify people and events from old newsreel footage and other films. Over time, the format changed a bit to include skits and musical performances. In January 1949 the series began airing on the CBS Eastern network. In April 1949, the series picked up a new sponsor (B.F. Goodrich), a new name (Celebrity Time), and a new network (it shifted to ABC). By that point, John Daly and Ilka Chase had become permanent panelists, joined each week by two guest panelists. Throughout all these changes, the series remained a Sunday night fixture.

Kyle served as a guest panelist on the July 10th, 1949 episode of Celebrity Time, with Lanny Ross the other guest. She returned for the February 12th, 1950 episode, alongside Max Baer and Maxie Rosenbloom. The series moved back to CBS beginning April 2nd. The following week, Kyle was a guest panelist again, this time with Hugh Herbert.

The New York Times reported on May 3rd that Kyle had been signed as permanent panelist, replacing Ilka Chase [50]. It is unclear when her first episode aired; it may have been the April 30th episode or the May 7th episode. She appeared in perhaps eight or nine episodes before Celebrity Time took a 13-week hiatus following its June 25th broadcast. During Kyle’s tenure on the series, if the male panelists answered a question correctly the prize money was donated to the Boy Scouts. If the female panelists answered first, it went to the Girl Scouts.

Kyle made good use of her time off. On July 19th she married television producer/packager Richard H. Gordon, Jr. in New York City. Their ceremony was officiated by State Supreme Court Justice Charles S. Colden at his chambers. A reception followed, after which the newlyweds left for their honeymoon in Bermuda [51].

Hold That Camera

A month before Celebrity Time returned from its summer hiatus, Kyle began hosting a half-hour weekly variety series called Hold That Camera on the DuMont Television Network. She replaced original host Jimmy Blaine. The series had started as a game show in which viewers at home could call in and team up with a member of the studio audience and face off against another viewer/audience team. The teams would play different games with the viewers at home directing their studio partners over the phone.

Hold That Camera had premiered on Sunday, August 27th, 1950 at 7:30PM as a sustaining program without a sponsor. It moved to Fridays at 8:30PM beginning September 15th and also picked up a sponsor: Esquire Boot Polish [52]. It was around this time that the series transitioned to variety — yet for some reason kept the original title — and Kyle took over as host. Television listings in The New York Times indicate that Kyle’s first episode on September 29th, although it may actually have been September 22nd or perhaps even September 15th to coincide with the format change and new day/time.

In addition to singing her own songs, Kyle acted as mistress of ceremonies, introducing performers visiting the “Camera Room” and participating in integrated commercials for Esquire products. Rex Marshall was the announcer for the series and also appeared in the commercials, having served as pitchman for Esquire since early 1950. The commercials also featured The Pastels, a singing quartet, and a basset hound named Morgan who belonged to Kyle and her husband (who served as co-producer on Hold That Camera). Holdovers from the original version included musical director Ving Merlin (and his Ving Merlin Orchestra) and writer Myron A. Mahler.

A review of the new Hold That Camera was published in the October 14th edition of The New York Times. Kyle was called “a welcome sight in front of any camera. She is at her best when singing, the rest of her performance seeming a little shallow and thus preventing her from being really outstanding” [53].

In late October, ABC expressed interest in acquiring the series from DuMont and approached Esquire about making the switch [54]. Esquire was reportedly concerned that DuMont wasn’t able to clear the show on enough stations but stayed put. Esquire would eventually drop its sponsorship of Hold That Camera after the December 15th episode [55].

Among the many guests who appeared on Hold That Camera were Joey Adams, Dick Haymes, Tito Guizar, Alan Dale, Fay MacKenzie, Clark Dennis, Larry Douglas, Jerry Wayne, Georgie Price, Johnny Coy, and Russ Emery. Roscoe Karns, who starred as Rocky King on DuMont’s live crime series Inside Detective (later known as Rocky King, Detective) made a brief appearance in one episode to promote his show.

Hold That Camera would be the last network television series hosted by Kyle.

A TV Career Winds Down

When Celebrity Time returned on October 1st, 1950 Kyle was back as the permanent female panelist and Herman Hickman had replaced John Daly as the show’s permanent male panelist. A former player, Hickman was head football coach at Yale University. Guest panelists for the first post-hiatus episode were Kitty Carlisle and Zachary Scott. Kyle remained with the series for six months, leaving in March 1951 to have her first child. The Billboard reported on March 24th that she would be replaced by Martha Wright beginning April 1st [56].

(Only days later, however, Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein decided they didn’t want Wright — who was scheduled to replaced Mary Martin in the Broadway production of South Pacific in June — to commit to a weekly television program [57]. Wright appeared in only a handful of episodes before Mary McCarty took over as the permanent female panelist. Celebrity Time remained on the air until September 1952.)

Kyle gave birth to a son in June 1951. By August, she was back on television. She made guest appearances on shows like DuMont’s Twenty Questions and Star of the Family on CBS. She also served as guest host for an episode of The Patricia Bowman Show, also on CBS. And she was reunited with her Girl About Town co-star Earl Wrightson when she appeared as a guest on the premiere of ABC’s At Home Show in late August, which Wrightson hosted.

In September, Kyle began serving as mistress of ceremonies for a local variety series in Pittsburgh called Welcome Aboard (a segment of WDTV’s Duquesne Show Time variety series, which rotated segments every week) [58]. She had been involved in kicking off the series in March 1951. Kyle’s segment was seen every four or five weeks. Although it remained on the air until April 1952, it is unknown how long Kyle was with the series.

Interlude: Radio, Film & Stage

After this initial burst of activity, Kyle’s television work slowed to a crawl. So she moved to radio and started hosting a 15-minute radio program (The Kyle MacDonnell Show) on station WOR in New York City. It debuted on Monday, January 28th, 1952. The program was heard from 6:15-6:30PM on Mondays, Wednesday, and Fridays. According to The New York Times, the radio program would included “chit cat and recorded music” [59].

In April 1952, Kyle was signed to a role in an upcoming Universal-International movie called The Great Companions, starring Dan Dailey [60]. Production was set to start in mid-May. The role was to have marked her screen debut but it didn’t work out. The film was later retitled Meet Me at the Fair and released in January 1953.

Coincidentally, Kyle did ultimately make her screen debut in a movie with Dan Dailey. She was signed in August 1952 to a featured part playing the fiancee of Dailey’s character in 20th Century-Fox’s Taxi [61]. It was also released in January 1953.

Aside from her radio show, Kyle kept busy performing, either solo or as part of a revue, at venues like the Empire Room at the Palmer House in Chicago; the Carousel and the Monte Carlo, both in Pittsburgh; and the Empire Room at the Waldorf Astoria in New York City.

Copyright © Bruno of Hollywood, 1955

She hoped to do more than just sing. “I’m not interested in doing the type of shows I’ve already been in,” Kyle told the Chicago Daily Tribune in April 1953. “I’m more anxious to take a plunge into acting. Musical comedy would probably be the best way since many of the singing parts require acting, too” [62].

She got her wish, appearing in a number of musical theater productions in 1952 and 1953, including the Pittsburgh Civic Light Opera Association’s production of “One Touch of Venus;” a touring production of “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes;” a touring production of “Twin Beds;” and even an ice show at the Roxy theater in New York City that accompanied the film Monkey Business.

Kyle wasn’t gone from television entirely. She made a January 1952 appearance on The Mel Torme Show on CBS and the following month was a guest on DuMont’s Stage Entrance. In May 1953, she made perhaps her sole television acting performance in an episode of ABC’s Plymouth Playhouse (also known for a brief time as ABC Album.

When her radio show ended in December 1953 so, too, it seemed, did most of her opportunities for work. In September 1954, Kyle performed at the Thunderbird in Las Vegas. The following month, she and her husband divorced. Aside from a handful of performances in the mid-1950s, she basically retired.

“Originally, I left television to have a baby,” she later explained in 1959. “When I tried to get back, it was difficult. I wasn’t in demand” [63]. Kyle moved to Kansas to raise her son near her parents. “I didn’t mind quitting at the time because I wanted to be with my son. We led a very quiet life. I played bridge with all the girls I grew up with — all of them married now with children. It was pleasant and relaxing — and dull, too, at times” [64].

A Life’s Work Lost

Kyle made a brief attempt at a comeback in 1959. She was a guest on the April 1st installment of NBC’s The Jack Paar Show, alongside Gloria Swanson, Don Adams, and Cliff Arquette. One critic, not familiar with her earlier television work, wrote “she sang like a bird and was the most attractive female singer I have seen since Marion Talley. Let’s hope Miss MacDonnell gets more work” [65].

News of her appearance on The Jack Paar Show led to a one-week theater engagement in early May and, more importantly, a guest appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show. The episode aired on Sunday, May 24th. Other guests included Ed Wynn, Carol Lawrence, and Fabian.

The comeback was short-lived. The two variety show appearances did not result in any additional television work for Kyle. Any disappointment didn’t last too long, however. On August 21st, she married William H. Vernon, president of the Santa Fe National Bank [66]. She retired again and this time it stuck. She lived in Santa Fe the rest of her life and remained married to Vernon until his death in 1995.

Kyle MacDonnell died in Santa Fe on September 28th, 2004 at the age of 82 [67].

Would Kyle’s career would have fizzled out even if she had not taken time off to start a family. There’s no way to know. Television in 1951 was still firmly in its vaudeo phase, with the networks offering plenty of comedy-variety and musical-variety programs every week. So it seems like there would have been a place for her somewhere. Yet the landscape of television had also changed drastically between 1948 and 1951. The number of television households in the country rose dramatically during those years as did the number of stations affiliated with the networks. Kyle’s association with NBC and its early regional networks was followed by a brief stint hosting a series on the DuMont network. After that, she served as a regular panelist on a CBS game show but never again hosted a network series.

Was there too much competition among singers capable of hosting their own television shows? Perhaps she was unwilling to take certain jobs or move to find work. Or maybe there something about Kyle that network executives or sponsors didn’t like, although that seems unlikely considering the critical acclaim she received.

Regardless, it is unfortunate that Kyle MacDonnell has been forgotten. Although her career didn’t last long she was absolutely one of television’s first stars. There are still a lot of unknowns about her, in large part because so little of her television work survives.

Including the shows she hosted or appeared on regularly and all of her guest appearances, Kyle made over 150 television appearances between 1948 and 1953 (plus two more in 1959). That’s a conservative estimate. Fewer than a dozen examples are known to exist today. No episodes of For Your Pleasure (in either of its incarnations) or Girl About Town have survived. Two episodes of Hold That Camera are extant, as are a few of her appearances on Cavalcade of Stars, plus several other programs she appeared on.

In January 2016, a brief fragment from an October 1950 episode of Celebrity Time was recovered. Although Kyle can be seen in the roughly six-minute excerpt, she doesn’t speak.

Hopefully, additional programs featuring Kyle are out there somewhere, in archives or personal collections, waiting to be discovered. She may not have played a huge role in the early days of television and like so many other singers, comedians, and actors from the late 1940s and early 1950s, her impact was limited. Yet she deserves to be remembered nonetheless as one of TV’s very first stars.

Works Cited:

2 Information on Kyle MacDonnell’s early life was compiled from a variety of newspaper and magazine articles, many of which were likely written using publicity material that may not have been entirely accurate. There may have been an attempt to conceal her true age from the public. For example, she would have just turned 26 in May 1948 when she appeared on the cover of Life, but her age was given as 23.

3 King Flynn, Joan. “How Kyle MacDonnell Got Into Television.” American Weekly [Insert]. 10 Jun. 1951: 25.

4 Gaver, Jack. “Broadway: Gotham Cowboys Form Texas Club.” Syracuse Herald-Journal. United Press. 18 Dec. 1945: 20.

5 “Dr. Joseph Lelyveld, Rockland Foot Specialist, Finds Models Have High Foot I.Q.” Daily Boston Globe. 30 Jul. 1946: 15.

6 Wolters, Larry. “A Pretty Face, Good Voice Got Kyle Into Video.” Chicago Daily Tribune. 4 Jun. 1950: N10.

7 King Flynn, Joan. “How Kyle MacDonnell Got Into Television.”

8 “Scott, John L. “Sh-h-h: Kyle MacDonnell Is Practicing First Role.” Los Angeles Times. 15 Jun. 1957: C1.

9 Ibid.

10 Wolters, Larry. “A Pretty Face, Good Voice Got Kyle Into Video.”

11 Pope, Virginia. “Polio Fund Holds Its Fashion Show.” New York Times. 28 Jan. 1948: 20.

12 Skutch, Ira. I Remember Television: A Memoir. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1990. Page 60.

13 Ibid.

14 “Television Find.” Life. 31 May 1948: 83.

15 Calta, Louis. “Perry Awards Due Tomorrow Night.” New York Times. 27 Mar. 1948: 10.

16 Brooks, Tim, and Earle Marsh. The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network and Cable TV Shows, 1946-Present. 8th ed. New York: Ballentine Books, 2003, Page 425.

17 Chase, Sam. “For Your Pleasure.” The Billboard. 1 May 1948: 11.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Gould, Jack. “A Pretty Girl.” New York Times. 2 May 1948: 89.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid.

25 Skutch. I Remember Television. 60.

26 “Television: The Infant Grows Up.”

27 Ibid.

28 “Television Find.”

29 Chase, Sam. “Are These TV MacNamees & Singin’ Sams?” The Billboard. 10 Jul. 1948: 3.

30 Ibid., 15.

31 “Radio and Television: Kyle MacDonnell to Be ‘Girl About Town’ When Program Bows Sept. 8 on WBNT.” New York Times. 17 Aug. 1948: 42.

32 “New Business.” Broadcasting. 23 Aug. 1948: 14.

33 “Radio and Television: Kyle MacDonnell to Be ‘Girl About Town’ When Program Bows Sept. 8 on WBNT.”

34 “Bates Fabrics On Television!” Bates Magazine. Nov. 1948: 17.

35 Ibid., 32.

36 Skutch. I Remember Television. 61.

37 According to Brooks and Marsh, Johnny Downs left Girl About Town “about a month after the program began,” suggesting he was replaced by Earl Wrightson as early as the October 6th or October 13th, 1948 episodes. Television listings in The New York Times first mention Wrightson on December 1st.

38 “Girl About Town.” Radio and Television Mirror. Mar 1949: 47.

39 Gould, Jack. “The Honor Roll.” New York Times. 26 Dec. 1948: X9.

40 Robertson, Bruce. “Coaxial Opening.” Broadcasting. 10 Jan. 1949: 30.

41 “Radio and Television: Washinton’s Inauguration Will Be Subject of Video Program on Network Tuesday.” New York Times. 19 Feb. 1949: 28.

42 [Advertisement]. New York Times. 27 Feb. 1949: 50.

43 “Radio-Video: Dr. Conant of Harvard to Discuss Education and Foreign Ideologies.” New York Times. 23 Jun. 1949: 54.

44 “On Television.” New York Times. 3 Jul. 1949: X8.

45 “Programs On The Air.” New York Times. 7 Jul. 1949: 50.

46 “Telecasting Network Showsheet: August.” Broadcasting. 25 Jul. 1949: 54-55.

47 According to Earl and Marsh, “During its final three months the program was known as Around the Town. A June 1949 article in The New York Times also uses this title. Other contemporary sources sometimes referred to the show as ‘Round the Town and All Around the Town.

48 “Radio and Television: Kyle MacDonnell Will Return in a New Video Program Over NBC Saturday at 8:30.” New York Times. 28 Jul. 1949: 44.

49 Atkinson, Brooks. “At the Theatre.” New York Times. 14 Oct. 1949: 34.

50 “Radio and Television: FM Station WABF to Present John Gielgud’s Recording of ‘Hamlet’ on Sunday.” New York Times. 3 May 1950: 58.

51 “Kyle MacDonnell Weds TV Director.” Schenectady Gazette. Associated Press. 20 Jul. 1950: 15.

52 “New Business.” Broadcasting*Telecasting. 8 Aug. 1950: 12.

53 “TV Hostess Played by Betty Furness.” New York Times. 14 Oct. 1950: 21.

54 “ABC Wooing Esquire to Move ‘Camera’ Seg.” The Billboard. 4 Nov. 1950: 4.

55 “Short Scannings.” Billboard. 23 Dec. 1950: 5.

56 “Production Notes and Personnel Activities.” The Billboard. 24 Mar. 1951: 44.

57 “Dick & Oscar Nix Singer’s TV Deal.” The Billboard. 7 Apr. 1951: 1.

58 Information about Kyle’s Welcome Aboard segment of WDTV’s Duquesne Show Time is sketchy. She was hosting the segment at least as late as November 1951, based on an entry in Harold V. Cohen’s “The Drama Desk” November 10th, 1951 column in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (Page 5)

59 “Bertrand Russell Agrees to TV Talk.” New York Times. 26 Jan. 1952: 19.

60 Pryor, Thomas M. “Aubrey Schenck Forms Film Firm.” New York Times. 22 Apr. 1952: 36.

61 Schallert, Edwin. “Drama: Billy De Wolfe Will Aid ‘Call Me Mada’ Fun; Craig to Rival Meeker.” Los Angeles Times. 12 Aug. 1952: B7.

62 Overholser, Martha. “Miss TV of ’48 Happy in Work as Club Singer.” Chicago Daily Tribune. 18 Apr. 1953: B1.

63 Torre, Marie. “Kyle MacDonnell Due As Paar Show Guest.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 31 Mar. 1959: 29.

64 Ibid.

65 Handte, Jerry. “Saroyan Can Be Funny.” Binghamton Press [Binghamton, NY]. 2 Apr. 1959: 40.

66 “Stage, TV Star Weds Banker.” Hartford Courant. Associated Press. 23 Aug. 1959: 12A.

67 “Actress Kyle MacDonnell dies at age 82.” United Press International. 1 Oct. 2004.

Image Credits:

2 From Radioland and Television, November 1948 (Vol. 1, No. 1), Page 92.

3 From an unidentified magazine, Page 37.

4 From Bates Magazine, November 1948 (Vol. 5, No. 2), Page 16.

5 Ibid.

Originally Published December 31st, 2014

Last Updated May 7th, 2018

Thank you so much for completing your overview of Kyle MacDonnell. What a great New Year’s Day present! I did not know of Ms. MacDonnell until I began reading about her on this site. Because of what you wrote, I have watched everything of her that is available on YouTube. She did have an excellent singing voice, and a likable, warm way about her. Yes, who knows what show business heights she could have achieved if she had not taken a break to have a baby, or if she were more ambitious. It could be that things would have turned out much the same way. The cold, hard fact of show business is that very few people make it to the top, and even fewer remain on top for decades. It is wonderful that you have helped to revive interest in Ms. MacDonnell, and that your article will keep her memory alive. Happy New Year to you and all your followers!

Fascinating stuff. Great work on this. I’m a big TV history guy, though my knowledge of really early TV is hazy. I had never heard of McDonnell before, but I’m always glad to come across articles like this.

The kind of fine scholarship the Internet makes possible. You should transfer this to a Wikipedia article.

I’m so happy to have found this article! My mother told me I was named after a “tall, blond and buxom” woman she and my father used to watch on tv in the late 1940’s. They both loved her and decided to name their first daughter after her. I am so grateful to not only get to read about her making life and many talents, but also get to see wonderful photos and listen to beautiful recordings. Thank you so muc!

Same! Altho’ after a fashion… My Mother’s (b. 1950) best childhood girl friend was named Kyle (likely after Kyle MacDonell) and I was named after her friend. I love my unique name and glad to find out more of its origin.

I too am a female Kyle! Named after Kyle McDonnell. I was told she was a great singer but that’s all. I’m so happy I found this article. She was a TV pioneer and very talented and beautiful.

Yes, thank you from me too. I was second born girl growing up in the Chicago suburbs in the 50’s. I was named Kyle Kerber. I always asked, “Why Kyle?” and dad said I was named after an actress/singer. Well I’ve found her. I married Jim Ziegler and now I also am Kyle Ziegler! REMARKABLE! Now I know my namesake.

I, too, was named after her! My mom watched The Jack Paar Show in 1959 and had me in 1960. Thank you for researching her history so throughly.

I enjoyed Kyle Ann Greene’s typo in her comment. It will be easy to see why.

I just noticed my error. I hope that Ms. Green will forgive my mistake.

This is a timely article as I have the May 31st. Issue of Life Magazine that you referenced. It is a nice article but your research adds much more background and together the two are perfect.

I am another female Kyle from suburban Chicago, who was named after Ms MacDonnell. My parents loved her voice. I am so happy to read about her life.!